House Competition: The Book of Concord

Wittenberg Academy's four houses, ranked according to the Book of Concord.

The Book of Concord

Martin Luther, Philip Melanchthon, Jacob Andreae, Martin Chemnitz, and Nicholas Selnecker—the authors of the Book of Concord—subscribed first to the Scriptures as the Word of Life, and next quoted the church fathers to support their confessions, showing that history lends credence to the one true faith.

The writers of the Book of Concord mention the church Fathers Ambrose, Augustine, Gregory and Jerome several times, along with several other lesser known saints.

The Saints

Ambrose of Milan lived from c. 339 to 397. A celebrated doctor of the Church and bishop of Milan from 374, he wrote many treatises on Christian life and doctrine. In 381, Saint Ambrose held a council at Milan against the heresy of Apollinaris, which reaffirmed the Nicene Creed and the true person of Christ. The feast day for Saint Ambrose is 7 December; the day of his appointment as bishop.

“The word of Christ could make out of nothing that which was not; can it then not change the things which are into that which they were not? For to give new natures to things is quite as wonderful as to change their natures.” ~St. Ambrose: On the Mysteries, 9, 52.

Augustine of Hippo lived from 354 to 430. Bishop of Hippo from 396 to his death, his works include famous titles such as Confessions and City of God. Saint Augustine laid the foundation for the Augustinian Order, which is an order of friars and nuns, and wrote extensively on the works of the Spirit. He is the patron saint of brewers, printers, and theologians1 and is celebrated in the church year on 28 August, the day of his death.

“That is true which is.” ~St. Augustine: Soliloquy ii, 5.

Gregory I, also known as Gregory the Great, lived from c. 540 to 604. He is best known for his development of Gregorian chant and monastic life, great liturgical contributions to the catholic church. His figure defines the historical bishopric of Rome, showing why the writers of the Book of Concord raise him up in contrast to the pope at the time of the Augsburg Confession. The feast of Saint Gregory falls on 3 September, the day of his episcopal consecration in 590.

“Study then, I beg you, and meditate daily on the words of your Creator. Learn the heart of God in the words of God, that you may sigh more eagerly for things eternal, that your soul may be kindled with greater longings for heavenly joy.” ~Pope St. Gregory I “The Great”: Letters 5, 46.

Jerome of Stridon lived from c. 342 to 420. He was first a monk in Syria, and then became a priest. In 382, he began work on the Vulgate: the official Latin text of the Holy Bible. Jerome translated the Old and New Testaments from the original Latin. Luther worked from this version of the Bible when he translated the Scriptures into his own German tongue. The day of commemoration for Jerome is 30 September, the day of his death.

“A man who is well rounded in the testimonies of the Scripture is the bulwark of the Church.” ~St. Jerome: Explanatio in Isaiam, 54, 12.

Some additional Saints featured in the Book of Concord are Chrysostom, Aquinas, Bernard, Francis, Cyprian, Cyril, and Justin; but, though they are certainly worthy of recognition, they do not come into this study.

Analysis

The Book of Concord begins with a preface, naturally, without any mention of our four saints. Andreae and Chemnitz wrote this preface themselves, listing a few conferences at which our confessions had been rejected. They cite several Bible verses, ultimately establishing an underlying hierarchy within the book. You will find that the Scriptures, presented faithfully as God’s very Word of Life, appear far more frequently than any quotes from the church fathers; and we would not have it any other way.

Included in the introduction to the Ecumenical Creeds, a note on church fathers: “The Augsburg Confession refers to ‘the Fathers,’ a reference to formative teachers in the history of the Church, most notably the Early Church Fathers who lived and worked between the first and fifth centuries.”2 Here we have both a definition of the Fathers of the church, and a commendation to pay heed to the lessons of history. Luther, Melanchthon, and the rest saw fit to include these Fathers many times, and so we see there is something to be learnt.

On to the Augsburg Confession! I do not intend to outline every single quote, but to give a sense of the way Luther and his contemporaries revered the church Fathers as great teachers and men of faith. The first mention of a canonical saint—besides the Blessed Virgin Mary—is of Ambrose in Article VI, New Obedience. His name comes up in relation to Luke 17:10, a verse on the duty of a servant towards his master: “We are unworthy servants; we have only done what was our duty.” The quote from Ambrose counterbalances this verse with the comfort of the gospel: “It is ordained of God that he who believes in Christ is saved, freely receiving forgiveness of sins, without works, through faith alone.”3 This confession is a wonderful beginning to the right reverence of the saints at which the Book of Concord aims. It also encapsulates the theological position of those standing by the Augsburg Confession at the time. Though the Lutheran princes did not know that the doctrine of Justification would in future be their ‘hill to die on’ (quite literally, since this was shown to be the defining issue in future controversies, and the princes were willing to risk martyrdom), from the very beginning they confessed true Law and Gospel. By displaying concord with Ambrose and other church Fathers, the princes showed that they were not cooking up some new heresy, as the papists claimed; they were endeavoring to reform the church; an attempt which, if unsuccessful, provided Lutherans with the best formula of the Christian faith out there.

The Augsburg Confession in its entirety mentions the Saints of our four houses twelve times, giving Ambrose four points, Augustine five, Gregory two, and Jerome one.

The Apology to the Augsburg Confession is, perhaps contrary to your first thoughts, not the product of a sniveling German writer coming up to the pontifical authorities saying, “Please forgive me, your eminence,” but rather a defense of the original confession. No article was taken back, recanted, or modified. The Apology addresses primarily the nature of the dissentions between the papists and the Lutherans, rather than basic theology, meaning practically that Article III Christ turns out to be shorter than Article IV Justification. These two articles exemplify the status of the controversy between Luther and Rome, even before there was a need for the Smalcald Articles: either faith in Christ justifies, or it does not. This brings us to our next highlight quote, from Augustine of Hippo. In On the Spirit and the Letter he says, “In a justified person, there is no right work by which he who does that work may live. But justification is received by faith.”4 These words perfectly show, not only the integrity of the Lutherans, but how skewed the papacy had become at this point. The Scriptures are clear: “For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast (Ephesians 2:8-9).”5

The whole Apology to the Augsburg Confession mentions our four Saints thirty-four times, leaving Ambrose with seven more points, Augustine with nineteen more, Gregory with three more, and Jerome with five more.

Next, the Smalcald Articles. In 1536, Paul III issued a formal decree for a general council to be held in Mantua, Italy (a council which never met). The document Luther prepared for this occasion was presented and discussed at the meeting of the Smalcaldic League, an association of Lutheran territories and cities formed in 1531.6 The Smalcald articles focus on the differences between Romanism and Lutheranism, and the three lengthiest articles are on The Mass, The Papacy, and Repentance, all addressing the Catholic Church’s corruption of the Sacraments. Luther does not quote any of our Saints directly in his articles, but mentions Jerome’s stance on earthly authority several times: “All the bishops should be equal in office. […] According St. Jerome, this is how priests at Alexandria governed the churches, together and in common.”7 This application of Jerome’s writings pertains to the Lutheran stance that the papacy exists only as a human institution. The bishop of Rome has only as much divine authority as every Christian bishop: the authority to bind and to loose on earth (Matthew 16:19).8

Throughout the Smalcald Articles, Luther mentions our house Saints five times: Augustine twice, and Jerome three times.

Luther himself did not attend the meeting of the Smalcaldic League, which resulted in the abandonment of his articles in favor of Melanchthon’s The Power and Primacy of the Pope. This treatise outlines the Roman misuses of the Scriptures and describes the correct role of bishops in the Church. Here Melanchthon cites a letter by Gregory I, “Pope Gregory, writing to the patriarch at Alexandria, forbids that he be called universal bishop. In the records he says that in the Council of Chalcedon the primacy was offered to the bishop of Rome, but it was not accepted.”9 This letter both proves Gregory’s humility and reveals the ludicrosity of the Catholic position in insisting on the supremacy of the pope.

In The Power and Primacy of the Pope, Melanchthon mentions our Saints five times, giving team Augustine one more point, team Gregory one more point, and team Jerome three more points.

The Small and Large Catechisms come after the Smalcald Articles and The Power and Primacy of the Pope; but these works cite only the Scriptures, which is very appropriate for books meant for the instruction of children, to be read and learnt by heart. Though Luther added a few things himself to the catechisms and approved when others did the same, the main portions of the Small Catechism were never essentially changed.10

Finally, the Formula of Concord. The Summary Content, Rule, and Norm of the Formula describes each issue at hand, first with affirmative statements of “pure teaching, faith and confession” and then with negative statements, which are “rejections of the false, opposite teachings.” The formula mainly addresses certain heresies and controversies pertaining to Christ and His work. The Formula of Concord, including the Epitome, mentions our four Saints thirteen times, leaving Ambrose with two more points, Augustine with nine more, and Gregory with two more.

Results

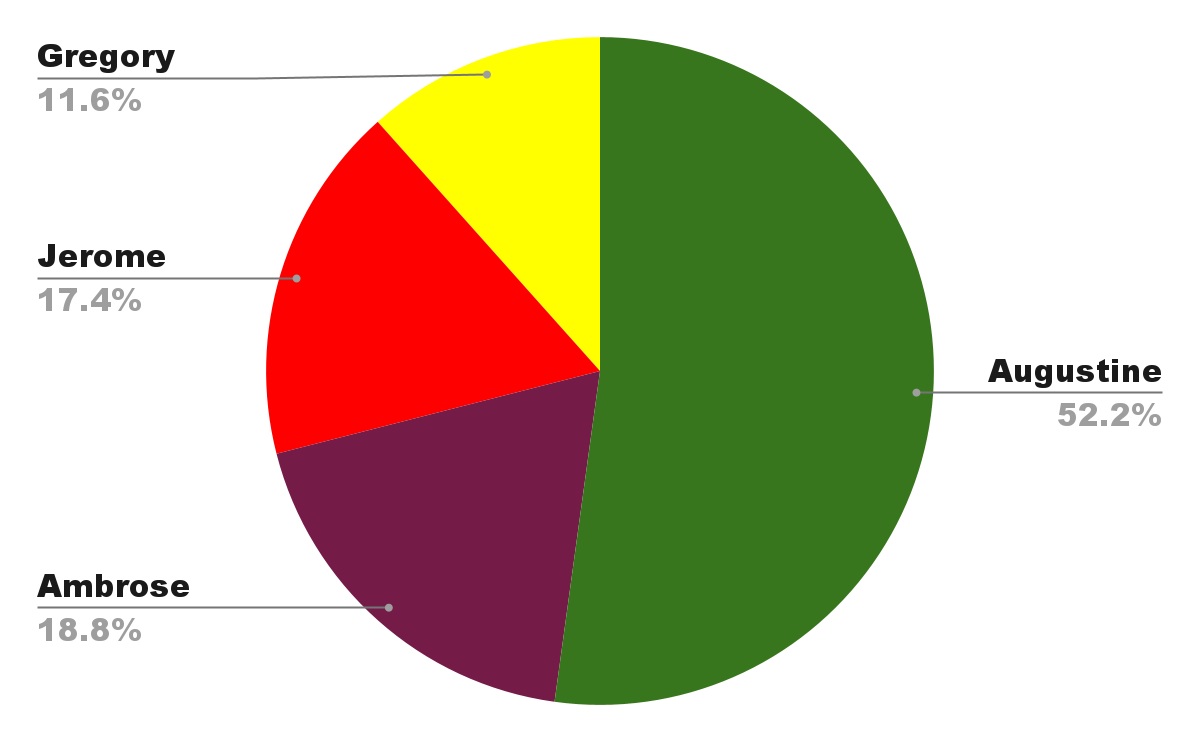

Ambrose House: 13 points

Augustine House: 36 points

Gregory House: 8 points

Jerome House: 12 points

This study is dedicated to Reverend Charles Henrickson, our Paideia III teacher, who fell asleep in Christ on April 17th of this year. Under his intrepid leadership, we had just finished Dr. Martin Luther’s Smalcald Articles and were discussing The Power and Primacy of the Pope by Philip Melanchthon. Soli Deo gloria.

No wonder Lutherans look up to him! Resource: https://www.visitstaugustine.com/article/how-st-augustine-got-its-name

Page 41. Reader’s Edition, CPH

Page 60. Reader’s Edition, CPH

Page 125. Reader’s Edition, CPH

English Standard Version. biblegateway.com

Page 281, 282. Reader’s Edition, CPH

Page 295. Reader’s Edition, CPH

English Standard Version. biblegateway.com

Page 322. Reader’s Edition, CPH

Page 337. Reader’s Edition, CPH